Technical Debt & Scalable Architecture: Why Fast Feature Delivery Today Becomes System Paralysis Tomorrow

Why 71% of growth-stage companies face a velocity cliff by Series B, and how to balance speed with scalability.

When a startup reaches product-market fit, the founder’s mandate is unambiguous: “Ship features faster than competitors.” The engineering team operates under relentless velocity pressure. New features are shipped weekly. Customer requests are triaged and prioritized. The codebase is modified to accommodate every new requirement.

In this environment, engineering leaders face a persistent trade-off: invest time in architecture (building systems designed to scale, anticipating future requirements, establishing patterns for consistent maintainability) or ship features faster. When the choice is between shipping a customer-requested feature in 2 weeks or building proper scalable architecture over 4 weeks, the founder invariably chooses the 2-week option.

This decision seems rational at small scale. Speed matters when product-market fit is uncertain and competition is intense. Yet this accumulation of speed-prioritized decisions over 18-36 months creates a technical debt crisis that becomes visible and existentially threatening exactly when growth accelerates and the company most needs engineering velocity.

In a comprehensive survey of 50+ growth-stage companies (Series A-C), 71% reported that technical debt had become a material constraint on engineering velocity by their Series B funding round. More concerning, 58% reported that technical debt issues had reached crisis levels, manifesting as development teams spending 40-50% of time on remediation, bug fixes, and workarounds rather than new feature development. This isn’t peripheral engineering management concern. For CTOs, technical leaders, and founders responsible for product delivery and competitive positioning, technical debt crisis represents an existential threat to company growth trajectory.

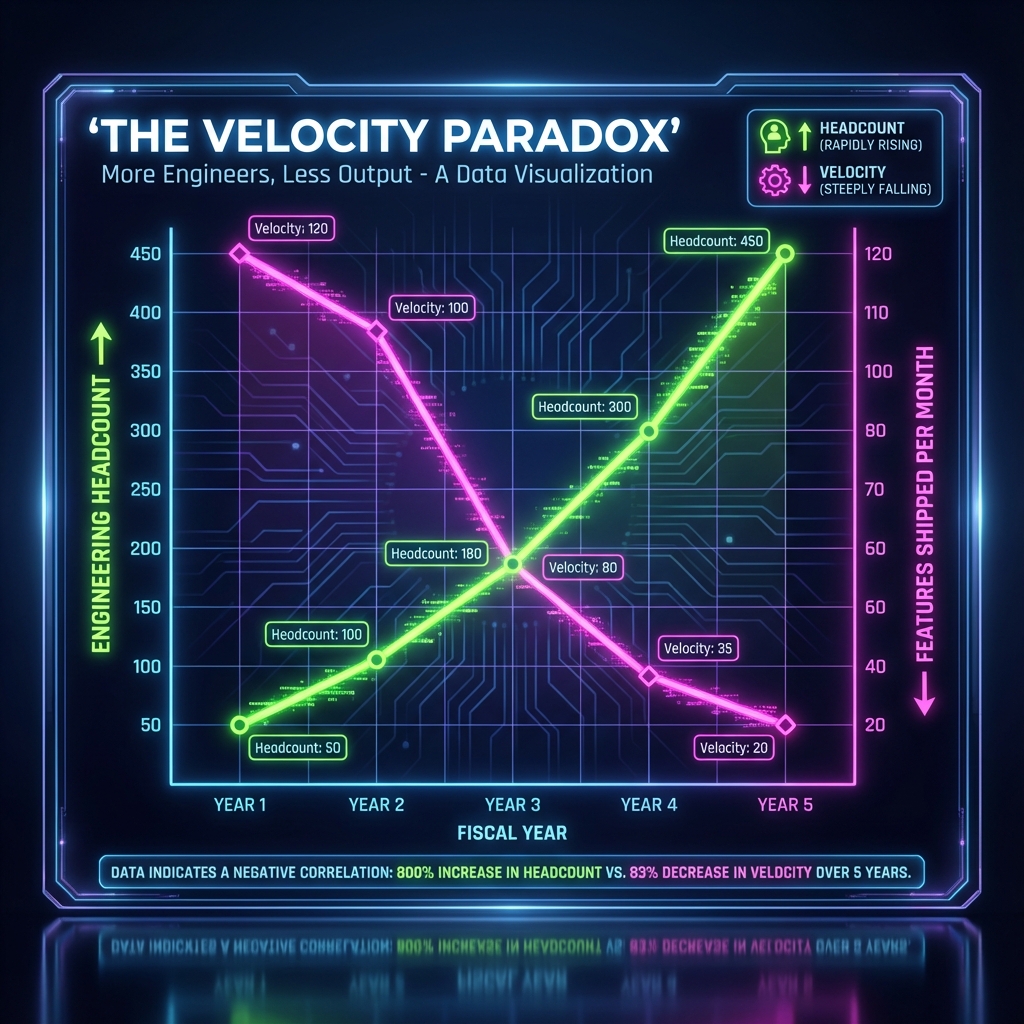

The problem manifests across multiple dimensions simultaneously: poor technology stack choices that create long-term friction, systems lacking the architectural foundation to scale, accumulated inconsistencies making the codebase increasingly difficult to navigate, bug rates accelerating as system complexity increases without corresponding quality investment, and most critically, development team velocity declining despite growth in headcount. The result is a company that shipped 10 features monthly at Series A but can only ship 3-5 features monthly at Series B—a 50-70% velocity decline despite 150-200% increase in engineering headcount.

For CTOs, engineering leaders, and operating partners responsible for maintaining or restoring engineering velocity, understanding why technical debt accumulates despite obvious costs, how it constrains growth, and what architectures and practices prevent it has become essential to competitive survival.

Why Technical Debt Accumulates: The Economics of Speed vs. Sustainability

Technical debt doesn’t accumulate from incompetence or neglect. It accumulates from rational economic decisions made under uncertainty, combined with a systematic underestimation of the long-term cost of short-term decisions.

The Speed Premium: Why Rapid Feature Delivery Is Economically Rational at Early Stage

At early stage (pre-Series A), engineering velocity is a primary competitive variable. A startup that ships new features 50% faster than competitors can:

- Test market hypotheses faster (ship feature, measure adoption, iterate or pivot)

- Respond to customer requests faster (maintain competitive advantage in customer satisfaction)

- Demonstrate progress to investors (investors see consistent feature delivery, perceive momentum)

- Attract engineering talent (engineers want to work at companies where they ship fast)

In this environment, investing 4 weeks in scalable architecture rather than 2 weeks in quick-and-dirty feature implementation is economically irrational. The company that prioritizes architecture ships 50% fewer features, tests hypotheses slower, and may not survive long enough to benefit from the architectural investment.

Early-stage investors and founders correctly optimize for speed. The venture capital model is predicated on finding companies with extreme growth potential; engineering velocity early stage is a proxy for growth potential. Speed is rewarded.

The Architectural Debt Accumulation Pattern: From Reasonable to Pathological

The accumulation follows a predictable pattern:

Months 1-6 (MVP Phase): The company has 3-4 engineers. The technology stack is deliberately simple: single-server architecture, monolithic codebase, basic deployment process. There’s minimal architectural debt because there isn’t much architecture. This is appropriate for MVP phase.

Months 7-18 (Product-Market Fit Search): The company has grown to 8-12 engineers. Revenue is emerging but not yet reliable. The company is hiring rapidly while iterating product. In this period, architectural decisions are made under uncertainty:

- Should we build microservices now or keep monolith? (Keeps monolith; microservices is “premature optimization”)

- Should we invest in API standardization? (Builds APIs organically; each service has different patterns)

- Should we build monitoring and logging infrastructure? (Prioritizes features; monitors as afterthought)

- Should we invest in automated testing? (Manual testing is faster initially; automation feels like overhead)

- Should we plan for database scalability? (Single database is simple; sharding can happen “later”)

Each individual decision is reasonable. Collectively, they create a system that works adequately at 10-50M monthly active users but isn’t designed for 100M+ users or 50+ engineers.

The codebase accumulates “shortcuts”: hardcoded values, duplicate logic, inconsistent patterns across services, basic error handling, minimal observability. The shortcuts work because the system isn’t yet at scale. But they create technical friction that manifests when scale increases.

Months 19-36 (Series B Scale Phase): The company has product-market fit, is raising Series B, and needs to scale. The engineering team grows from 12 to 40+ engineers. The mandate is to accelerate feature delivery, expand into new markets, and build new product lines.

In this phase, the accumulated architectural shortcuts become problematic:

- The monolithic architecture that was fine for 50M users causes deployment bottlenecks at 200M users. A deploy takes 30 minutes; if there’s a bug, rollback takes another 30 minutes. The company can’t ship multiple features daily anymore.

- The inconsistent API patterns create friction when new engineers join. Each engineer spends 1-2 weeks learning “how we do things here” because “how we do things” isn’t standardized. Onboarding slows.

- The lack of monitoring infrastructure means that when performance degrades, the team spends 4 hours investigating the root cause. If there’s a production outage, recovery takes hours because debugging infrastructure is minimal.

- The database that was a single PostgreSQL instance becomes a bottleneck. Scaling requires sharding, which requires significant engineering investment (3-6 months) that wasn’t planned for.

- The accumulated duplicate logic and shortcuts create a codebase that’s increasingly difficult to modify without creating bugs. Features that would have taken 1 week at Series A now take 3 weeks because the engineer must navigate inconsistent patterns and undocumented design decisions.

In this phase, technical debt transitions from invisible (the shortcuts worked fine at small scale) to visible and expensive (the shortcuts now constrain growth). The company faces a choice: invest heavily in architectural remediation (3-9 months of engineering time) or accept continued velocity degradation.

Most companies at this phase have already committed capital to Series B with assumptions about engineering velocity. They’re under pressure to deliver against those commitments. Pausing feature development for 3-6 months of infrastructure work feels like a luxury they can’t afford. So they continue shipping features, accepting slower velocity.

The False Choice: Speed vs. Scalability as Immovable Constraint

Many engineering leaders frame technical debt as an unavoidable trade-off: “You can either ship fast or build scalable systems; you can’t do both.” This framing is incorrect. More accurately, the trade-off is between investing in scalable systems early (when the investment feels expensive relative to immediate payoff) vs. investing in scalable systems late (when the investment becomes critical but also much more expensive).

Consider database scalability:

- Early-stage approach (Series A): Single PostgreSQL database. The company can scale to 10-50M users with a single database through optimization (indexing, caching, query optimization). The company doesn’t invest in sharding.

- Late-stage remediation (Series B): The database is maxed out. The company must implement sharding. This requires: (a) designing shard key strategy, (b) migrating existing data to shards, (c) updating application logic to route queries to correct shard, (d) implementing cross-shard consistency logic. This is 4-6 months of engineering work.

Cost of late remediation: 1-2 engineers for 4-6 months = $600K-$900K in engineering cost, plus opportunity cost of those engineers not building product.

Compare to:

- Early-stage investment (Series A): At Series A, the company invests 4-6 weeks in designing a sharding strategy and building sharding abstraction layer. Cost: $50-100K in engineering time.

Cost differential: Late remediation costs 6-9x more than early investment.

The same pattern repeats across API standardization, monitoring infrastructure, testing automation, and deployment automation. Early investment in these areas feels expensive ($50-150K per area) but prevents 10x more expensive late remediation ($500K-$2M per area when crisis-driven).

Yet venture-backed companies systematically underinvest in early-stage infrastructure because Series A investors optimize for revenue growth, not architectural purity. The founder who proposes investing $200K in infrastructure (4-6 engineers for 8-10 weeks) hears: “That’s not ambitious enough. We should invest that engineering capacity in product and customer acquisition.” Investor incentives push toward product and away from infrastructure.

The Compounding Problem: Technical Debt Attracts More Debt

An overlooked dynamic: poor technical decisions early attract more poor decisions later. The reasoning is logical but creates perverse incentives:

When a company has already made the decision to build a monolithic architecture rather than microservices (a structural choice that was reasonable at the time but suboptimal at scale), the company is then biased toward making additional decisions that work with the monolith rather than requiring architectural refactor.

A feature that would naturally be a separate microservice gets built as a monolithic module because “refactoring to microservices would delay the feature.” A caching layer that would naturally be implemented via distributed cache gets hacked via local in-memory cache because “implementing distributed cache would delay the feature.” An operational concern (multi-tenancy, compliance, observability) gets built as a bolt-on rather than architectural principle because “building it the right way would delay the feature.”

Each subsequent decision, made individually, is rational. Collectively, they compound the original architectural decision, making the system progressively less adaptable. Six months into Series B, the company has a monolithic architecture with 20 bolt-on modifications, inconsistent patterns across the codebase, and an engineering culture where “ship fast” routinely overrides “build sustainable systems.”

This creates a cultural issue: engineers learn that cutting corners and shipping fast is rewarded. The engineer who ships a feature in 2 weeks (cut corners) is praised. The engineer who ships a feature in 4 weeks (did it right) is questioned about why it took longer. Over 12-18 months, this culture propagates. New engineers hired at Series B have been trained in cutting-corner culture. They continue the pattern.

Reversing this cultural pattern is extremely difficult. It requires not just technical remediation but cultural change: rewarding engineers who build sustainable systems, penalizing engineers who create additional technical debt, and investing in infrastructure despite short-term velocity cost.

The Value Destruction Cascade: How Technical Debt Constrains Growth and Accelerates Decline

The impact of technical debt accumulation compounds across multiple dimensions that interact destructively.

Constraint 1: Velocity Degradation Despite Increasing Headcount

The most visible consequence: engineering velocity declines even as headcount increases.

A typical pattern in technically debt-laden companies:

- Series A (12 months prior): 8 engineers, shipping 10 features monthly (1.25 features per engineer per month). Codebase is 150K lines of code.

- Series B close: 8 engineers still (hiring takes time), shipping 10 features monthly. Codebase is 200K lines of code (25% growth).

- 6 months post-Series B: 25 engineers (212% increase in headcount). Shipping 8 features monthly (20% velocity decline despite 212% headcount increase). Codebase is 400K lines of code (100% growth in 6 months).

- 12 months post-Series B: 40 engineers (400% increase vs. Series A). Shipping 5 features monthly (50% velocity decline). Codebase is 550K lines of code (183% growth).

The velocity degradation manifests as:

- Reduced engineer productivity: When each engineer was shipping 1.25 features monthly, each engineer now ships 0.125 features monthly. This isn’t because new engineers are incompetent; it’s because navigating the codebase requires time, understanding architectural decisions requires context, and making modifications creates risk of breaking existing functionality.

- Increased coordination overhead: At 8 engineers, feature development has minimal coordination overhead. At 40 engineers across 4-5 feature teams, coordination overhead is substantial. Feature teams must coordinate with each other, manage shared component ownership, negotiate over infrastructure investment, and manage dependencies.

- Increased debugging and remediation time: The codebase that had 5-10% defect escape rate now has 15-25% defect escape rate because code changes have more subtle interactions. More production bugs means more time spent debugging and fixing rather than developing new features. A developer might spend 30% of their time on bug fixes at Series A but 50%+ of their time on bug fixes at Series B.

- Increased onboarding friction: New engineers take 4-6 weeks to become productive at Series A but 8-12 weeks at Series B because architectural inconsistencies require more time to understand. The company that was hiring 1-2 engineers monthly and achieving productivity in 4-6 weeks is now hiring 4-5 engineers monthly but achieving productivity in 10-12 weeks. The onboarding queue becomes a bottleneck.

For a company that was shipping 10 features monthly with 8 engineers, this velocity degradation is devastating. The product roadmap assumed 10 features monthly at Series B to capture market opportunity. The company can now only ship 5 features monthly. The company is shipping 50% fewer features than planned, which translates to 50% slower time-to-market for new product, 50% slower ability to respond to competitive threats, and 50% slower ability to acquire customers through product innovation.

Over 12-18 months, this velocity degradation compounds. Competitors who maintained technical discipline and architectural coherence are shipping 10-15 features monthly. The technically debt-laden company is shipping 5-8 features monthly. By Series C, the gap is clear: the technically disciplined company has 2-3x market share, 2-3x more customer relationships, and significantly better product moat.

Constraint 2: Bug Rates and Production Reliability Degradation

Technical debt creates an environment where bugs accumulate and production reliability declines.

This manifests through multiple mechanisms:

- Reduced test coverage: Early-stage companies often build test infrastructure gradually. A company that was disciplined about testing might have 70-80% code coverage at Series A. A company that deferred testing infrastructure while prioritizing features might have 30-40% coverage. When the company grows to Series B, the sparse test coverage means that new engineers can’t understand whether their changes break existing functionality. They deploy to production, discover bugs in production, then revert changes. This cycle increases cycle time and reduces productivity.

- Increased architectural complexity without increased understanding: As technical debt accumulates, the codebase becomes internally inconsistent. A database query in Service A uses a pattern that’s different from the pattern in Service B. An API endpoint in Module X has error handling that’s different from the error handling in Module Y. When a new engineer modifies code, they don’t understand why the inconsistency exists. They copy the existing pattern, perpetuating the inconsistency. The codebase becomes progressively less coherent.

- Undocumented design decisions: Early-stage companies make architectural decisions (choice of database, choice of cache layer, choice of message queue) and document them poorly. As the company grows, new engineers don’t understand why these choices were made. They see the resulting system and think “this is a bad choice” without understanding the constraints that made it optimal at the time. They propose refactoring to what they consider a better technology. Debate ensues. The company invests engineering time debating technical choices rather than building features.

- Accumulated workarounds and hacks: Over 18-36 months of rapid feature development, engineers accumulate workarounds: hardcoded values that should be configurable, duplicate logic that should be consolidated, temporary solutions that should be permanent. Each workaround was created to ship a feature faster. Each workaround lives in the codebase as technical debt. When the next engineer encounters the workaround, they often don’t understand it, create a parallel workaround rather than consolidate, and the codebase accumulates more debt.

- Monitoring and observability gaps: Early-stage companies often lack comprehensive monitoring and logging. When a bug manifests in production, the team spends hours investigating root cause because they lack observability. The bug might be a performance issue, a data consistency issue, or a race condition. Without logs and metrics, the team is blind. They must reconstruct what happened by looking at database snapshots and user reports.

The cumulative impact: a company that had <5 P0 incidents monthly at Series A has 3-4 P0 incidents weekly at Series B. Each incident consumes 4-8 hours of engineering time (investigation, fix, rollout, post-mortem). For a company with 40 engineers, this represents 400-800 hours monthly of incident management. That’s equivalent to 2-4 FTE devoted to incident response rather than feature development.

Constraint 3: Engineering Talent Attrition and Difficulty Recruiting

Technical debt creates an engineering environment where talented engineers don’t want to work.

Multiple dynamics:

- Reduced shipping satisfaction: Engineers join startups partly for the satisfaction of shipping products fast. When a technically debt-laden company slows to shipping 5 features monthly (vs. 10 features monthly at a healthy company), the shipping satisfaction declines. Engineers feel they’re not progressing, not building exciting things. Retention declines.

- Frustration with working in poor codebase: Engineers with options don’t want to work in codebases that are difficult to navigate, inconsistently structured, and fragile. A talented engineer who could build a feature in 1 week in a clean codebase but takes 3 weeks in a debt-laden codebase is frustrated. They’re not being productive; they’re fighting the system.

- Difficulty recruiting: When the CTO tells a candidate “we have some technical debt in our codebase,” the candidate nods politely. But when the candidate interviews with existing engineers and hears “our codebase is a mess,” “it takes weeks to understand how a new feature should be built,” “our deployments are fragile,” the candidate recognizes this as a negative signal. The company loses talented candidates to competitors with better codebases.

- Key technical leader departure: The CTO or VP Engineering who built the early system and understands the architectural rationale is often the first person to burn out from working in a deteriorating codebase. They see the debt accumulating, repeatedly advocate for infrastructure investment, and get deprioritized. Frustration builds. They leave for opportunities where their expertise in building scalable systems is valued.

When the CTO/VP Engineering leaves, the company loses institutional knowledge about why architectural decisions were made, what had been attempted, and what the debt remediation strategy should be. A new technical leader arrives, looks at the debt, and proposes a comprehensive rewrite. The company is now in crisis remediation mode rather than steady-state engineering.

The talent impact is substantial: a company losing 30-40% of engineers annually due to working in technically debt-laden environment experiences turnover that accelerates remaining retention. By Series B or Series C, the engineering team is depleted.

Constraint 4: Inability to Modernize or Pivot

A technically debt-laden system is inflexible. When market conditions change or the company needs to pivot product strategy, the codebase constrains options.

Example: A SaaS company built a single-tenant architecture where each customer has a separate database. The company’s go-to-market was built on this model (selling multi-user SaaS to teams). Two years in, the company discovers that enterprise customers want multi-tenant SaaS where they can manage multiple departments in a single instance. Converting from single-tenant to multi-tenant is a major architectural shift: the entire data model must change, the authentication system must change, the billing system must change, the feature logic must change.

In a clean, modular architecture, this might be achievable in 4-6 months with proper planning. In a technically debt-laden codebase, this might require 9-12 months or become impossible without a rewrite.

The company faces a difficult choice: (1) Invest 9-12 months in architectural remediation (foregoing all feature development, all customer acquisition), (2) Build a parallel multi-tenant system (doubling infrastructure complexity and maintenance burden), or (3) Accept that the market opportunity for multi-tenant SaaS is inaccessible and focus on single-tenant market.

A well-architected company has built the system to support multi-tenant in the future (even if not used currently). The company can add multi-tenancy in 4-6 weeks by activating the dormant capability. A debt-laden company doesn’t have this option.

Constraint 5: Increased Infrastructure and Operational Costs

Technical debt accumulates operational costs that aren’t visible on the income statement but represent real cash expenditure.

Multiple dimensions:

- Infrastructure costs: A poorly optimized codebase consumes more infrastructure resources. A API endpoint that should execute in 100ms but executes in 500ms due to inefficient queries consumes 5x the cloud infrastructure. A company that could run on 10 cloud instances might need 50 instances due to inefficiency. The annual infrastructure cost difference might be $500K-$2M.

- Hosting and scaling costs: A company that didn’t invest in efficient database design might need to implement expensive caching layers, expensive read replicas, or expensive sharding infrastructure. These operational solutions add significant infrastructure costs rather than addressing the root architectural issue.

- External consulting and contractor costs: When technical debt reaches crisis level, companies hire expensive contractors or consulting firms (Accenture, Deloitte, smaller technical shops) to help remediate. These engagements cost $500K-$5M depending on scope. If the company had made disciplined architectural decisions early, these costs would have been zero.

- Managed services subscriptions: Companies struggling with infrastructure management often subscribe to managed services (managed databases, managed Kubernetes, managed CI/CD) to reduce operational burden. These services cost 3-5x more than self-managed infrastructure but enable companies without infrastructure expertise to operate systems. The cost differential might be $200K-$500K annually.

The cumulative infrastructure cost difference between a clean, efficient architecture and a debt-laden, inefficient architecture might be $1-3M annually. For a Series B company, this represents 5-15% of annual operating budget.

Why Technical Debt Problems Persist: Structural Barriers to Fixing the Problem

Given the obvious costs of technical debt, why do growth-stage companies persist in accumulating it rather than investing early in scalable architecture?

Venture Capital’s Emphasis on Growth Metrics Over Engineering Discipline

Series A and Series B investors evaluate companies primarily on revenue growth and user growth metrics. Investor pitch decks emphasize: revenue growth rate (%), month-over-month growth, total addressable market (TAM), competitive positioning, unit economics.

Investor pitch decks don’t emphasize: code coverage, architectural coherence, technical debt inventory, infrastructure investment roadmap. These metrics are boring and irrelevant to investors’ core thesis.

This creates misaligned incentives. A founder who proposes slowing feature development for 2-3 months to invest in architecture hears: “That’s not aggressive enough. You’re leaving market opportunity on the table.” Investors fear that the company will lose competitive ground to better-capitalized competitors who prioritize growth.

This investor perspective is reinforced by the selection effect: companies that prioritize growth over engineering discipline grow faster in the short term (first 18-24 months), which makes them more visible to investors and more likely to raise subsequent funding. Companies that invest in architecture early grow more slowly initially but compound faster over 3-5 years. The selection effect favors the short-term growth maximizers.

Founder Bias Toward Visible Progress

Founders are rewarded for shipping features and demonstrating growth. Investors celebrate when a company ships 10 features monthly and grows 20% month-over-month. They don’t celebrate when a company invests 2 months in infrastructure that will enable 3x faster development in 18 months.

This creates a powerful psychological bias: founders want to see visible progress. Features are visible progress. Infrastructure investment feels like a tax on progress.

Additionally, the founder of a company in growth-stage scaling (Series A or Series B) may not have experience with technical debt consequences. They’ve never led a company through the velocity cliff that occurs when debt becomes critical. They’re operating on intuition that “we’ll invest in infrastructure later when we’re profitable” rather than understanding the cost curve of deferred investment.

CTO Authority Limits and Technical Decision Misalignment

In many growth-stage companies, the CTO advocates for architecture investment but lacks authority to enforce it. The CTO reports to the CEO. The CEO is focused on revenue growth and investor relations. The CEO prioritizes features over infrastructure.

The CTO might propose: “We should spend 2 months building a multi-tenant capability into our data model so we can support customers with multiple departments. This will unlock $500K in new enterprise revenue.” The CEO hears: “You want to slow down and not ship features for 2 months.” Even though the CTO framed it as a revenue enabler, the CEO’s mental model is feature velocity.

Over time, the CTO’s infrastructure recommendations are deprioritized repeatedly. The CTO either accepts this (stops advocating) or becomes frustrated and leaves. When strong CTOs leave technical debt-laden companies, the technical discipline deteriorates further.

Difficulty Quantifying Long-Term Benefit of Infrastructure Investment

Engineering leaders can’t precisely quantify the benefit of infrastructure investment, which makes it hard to justify. A CTO might say: “If we invest in improving our deployment pipeline, we’ll reduce deployment time from 30 minutes to 5 minutes and enable 3x more deployments daily.” But translating this to business impact is indirect: faster deployments → more frequent feature releases → incrementally faster time-to-market → incrementally more customer adoption.

The business impact is real but diffuse. It’s hard to say: “This infrastructure investment will result in $2M of incremental revenue.” It’s easier to say: “If we build this feature, we’ll acquire 10 new customers worth $500K annually.”

This quantification gap means infrastructure investment is often underfunded relative to its impact, even by technical leaders who understand the long-term consequences.

The Framework: How to Build and Maintain Scalable Architecture at Growth Stage

Growth-stage companies that systematically address technical debt avoid the velocity cliff and transform technical discipline into competitive advantage. Several patterns distinguish companies with scalable architecture from those with debt-laden systems.

Principle 1: Technology Stack Decisions Are Made With 10-Year Horizon, Not 6-Month Horizon

High-performing engineering organizations make technology stack decisions expecting that the choice will be used for 5-10 years, not 18 months.

This doesn’t mean using the “perfect” technology. It means using technologies that:

- Have sufficient community support and adoption that they won’t become obsolete

- Have sufficient operational maturity that the company won’t spend inordinate time on infrastructure

- Have sufficient flexibility that the company can build the range of features anticipated for 5+ years without fundamental architecture redesign

Example decisions:

- Database choice: A company choosing between PostgreSQL and MongoDB makes a 10-year decision. PostgreSQL is mature, widely supported, and handles relational data well (at scale) and unstructured data adequately. MongoDB is specialized for document storage but less mature for complex transactions. The company that chooses PostgreSQL is betting that relational storage will be adequate for their use cases for 10 years. This is usually true. The company that chooses MongoDB is betting that document storage is superior to relational storage for their use cases for 10 years. This is sometimes true, sometimes not.

- API architecture: A company choosing between monolithic (all APIs in one codebase) and microservices (separate services with their own APIs) makes a 10-year decision. Monolithic is simpler initially but harder to scale beyond 20-30 engineers. Microservices is complex initially but enables scaling beyond 50+ engineers. A company anticipating 30+ engineers by Series B should lean toward microservices. A company anticipating 10-15 engineers should lean toward monolithic.

- Deployment infrastructure: A company choosing between simple deployment (scripts running on EC2 instances) and containerized deployment (Docker/Kubernetes) makes a 10-year decision. Containerized deployment is complex initially but enables scaling to 100+ services. Simple deployment is fast initially but constrains scalability.

High-performing companies explicitly reason about these decisions with a 10-year horizon. They acknowledge that the choice will constrain options for 5-10 years. They choose technologies with sufficient flexibility.

Principle 2: Technical Debt Is Explicitly Tracked and Managed Like Financial Debt

High-performing companies maintain a technical debt inventory and make deliberate decisions about remediation, not allowing debt to accumulate invisibly.

This includes:

- Debt inventory: The company maintains a list of known technical debt (architecture that should be refactored, code that should be rewritten, infrastructure that should be improved, undocumented systems). Each debt item includes: (a) description, (b) estimated remediation cost, (c) estimated business impact if not remediated (risk: performance degradation, reliability issues, maintainability issues), (d) priority.

- Quarterly debt remediation: Each quarter, 10-20% of engineering capacity is allocated to debt remediation. This is non-negotiable (not “if we have time” but “this is allocated capacity”). The allocation is determined by: highest-impact debt (biggest business risk), fastest-remediable debt (can get quick wins), and deliberate debt reduction trajectory.

- Debt payoff metrics: The company tracks debt remediation progress. How much debt was remediable? How much new debt was created? Is net debt decreasing? If net debt is increasing despite 20% remediation allocation, the company is creating debt faster than remediating it—a sign that development practices need to change.

- Debt prevention: The company establishes practices to prevent new debt creation: code review standards that catch architectural debt before merge, architectural reviews for major features, testing standards that prevent quality debt.

Principle 3: Architectural Decisions Are Made Deliberately, Not Organically

High-performing companies establish an architectural review process where major decisions (new services, new databases, new infrastructure, significant refactors) are reviewed for:

- Consistency with existing architecture

- Scalability constraints (does this decision constrain future scaling?)

- Operational burden (does this introduce new operational responsibilities?)

- Reversibility (can we undo this decision if it turns out to be wrong?)

This process isn’t bureaucracy; it’s discipline. The CTO or lead architect reviews major decisions and asks probing questions. Engineers propose architectures and defend them against future scenarios.

The outcome: the company avoids the organic architecture pattern where each team makes independent decisions that don’t align with each other. The company instead has coherent architecture where decisions build on each other.

Principle 4: Monitoring, Logging, and Observability Are Built In, Not Bolted On

High-performing companies invest in observability infrastructure early (first 6-12 months), not after problems manifest.

This includes:

- Structured logging: Every service logs events in a consistent, structured format that enables searching and aggregating across services. When a problem occurs, engineers can query logs across all services to trace the issue.

- Metrics and monitoring: Every service exposes metrics (request count, latency, error rate, business metrics) that are collected and visualized. Engineers can see system behavior in real-time and detect degradation.

- Distributed tracing: A single user request often traverses multiple services. Distributed tracing enables engineers to see the full request path and identify where latency or errors occur.

- Alerting: Systems are configured to alert engineers when metrics exceed thresholds (error rate spikes, latency increases, disk usage warning). Alerts enable fast detection of issues before they become critical.

A company that invests $100K-$200K in observability infrastructure in first 12 months later saves $500K-$2M in debugging costs, incident response costs, and capability development costs (engineers spend less time investigating and more time building).

Principle 5: Testing Is Comprehensive, Not Sparse

High-performing companies invest in testing infrastructure and maintain high test coverage (70%+) rather than relying on manual testing.

This includes:

- Unit tests: Developers write unit tests for code they write. The test suite runs on every merge and prevents obvious bugs from reaching production.

- Integration tests: Systems that have multiple components (frontend, backend, database) have integration tests that verify components work together.

- Automated deployment tests: The deployment pipeline includes tests to verify that deployments succeed and don’t introduce regressions.

- Performance tests: Performance-critical systems have tests that verify performance hasn’t degraded.

A company with comprehensive testing spends more time on testing infrastructure initially (20-30% of initial development) but experiences 40-50% fewer production bugs long-term. The velocity benefit compounds over time: the company ships 20% slower initially but ships 50% faster long-term because time spent debugging and fixing bugs is eliminated.

Principle 6: Engineering Culture Values Sustainable Development

High-performing companies establish engineering culture where building sustainable systems is valued and cutting corners is penalized.

This is achieved through:

- Manager behavior: Engineering managers recognize and celebrate engineers who build sustainable systems, even if it takes longer. They counsel engineers to “do this right” rather than “move fast and break things.”

- Hiring: During hiring, the company emphasizes architectural thinking and long-term vision, not just “can ship fast.” Questions like “Tell me about a system you built that you’re proud of architecturally” reveal whether candidates value sustainability.

- Code review: Code reviews emphasize architectural consistency and maintainability, not just “does it work.” Reviewers push back on technical shortcuts.

- Decision-making: When faced with speed-vs.-sustainability trade-offs, the company frequently chooses sustainability (even if it delays feature delivery by 2-3 weeks).

This culture shift is subtle but profound. A company with “ship fast” culture accepts cutting corners. A company with “ship sustainably” culture questions cutting corners. Over 18-24 months, the cultural difference accumulates to 2-3x difference in velocity.

Principle 7: CTO/Technical Leadership Authority Is Explicit

High-performing companies establish that the CTO has explicit authority over technical decisions and can override velocity-driven requests if they violate architectural standards.

This doesn’t mean CTO has veto over all decisions. It means: (a) the CTO has authority to establish and enforce architectural standards, (b) when product leadership wants to build something in a way that violates standards, the CTO’s perspective is weighted heavily, (c) the CEO supports the CTO when architectural discipline requires deferring features.

A CEO saying “this feature needs to wait 2 weeks for proper architecture” and CTO backing is how sustainable architecture is preserved. A CEO saying “ship it fast, we’ll refactor later” overriding CTO objections is how technical debt accumulates.

Principle 8: Fractional CTO/Architecture Advisory for Technical Debt Remediation

Here’s where this connects to fractional CTO services.

For companies where technical debt has reached crisis levels (velocity cliff is evident, 40-50% of engineering time is spent on remediation), the highest-impact intervention is fractional CTO or technical architecture advisory for 6-12 months.

Here’s why this is valuable:

- External perspective and credibility: A fractional CTO with experience at 20-30 growth-stage companies has seen technical debt patterns and recovery patterns. They can provide perspective on: (a) severity of current debt situation, (b) prioritization of remediation, (c) realistic timeline for recovery.

- Technical debt prioritization: The fractional CTO works with the internal technical team to inventory debt, assess business impact, and prioritize remediation. They identify the 20% of debt that delivers 80% of business benefit when remediated.

- Architecture and remediation planning: The fractional CTO designs the remediation approach: which components should be refactored, which should be replaced, what’s the sequence? They create a roadmap that balances velocity recovery with feature delivery.

- Engineering team development: The fractional CTO mentors the internal technical team, establishing sustainable practices (testing, code review, architectural standards) that prevent new debt accumulation.

- Executive alignment: The fractional CTO communicates to leadership the cost of technical debt, the business impact of velocity recovery, and the investment required. They help CEO understand why 2-3 months of reduced feature development is necessary for long-term velocity recovery.

- Hiring and scaling guidance: As the company is remediating debt and scaling engineering, the fractional CTO advises on hiring (what skills to prioritize), structure (how many teams, what size), and process (what practices enable scaled development).

For a growth-stage company experiencing 50% velocity decline due to technical debt, a fractional CTO ($20K-$30K monthly for 6-12 months) can identify $2-10M in business value recovery through reduced incident response time, improved velocity, reduced infrastructure costs, and improved product quality. This delivers 20-100x ROI.

Actionable Recommendations for Growth-Stage Companies

Based on current research and sustainable architecture best practices, CTOs and technical leaders should:

-

Establish Technology Stack and Architecture Decisions With 10-Year Horizon Rather than optimizing for initial speed, evaluate technology choices for long-term flexibility:

- Document technology stack rationale (why PostgreSQL? why Kubernetes? why this API pattern?)

- Explicitly consider scalability constraints for each decision (what happens at 10M users? 100M users? 1B users?)

- Establish that significant architecture changes require CTO approval and business impact justification

-

Maintain Technical Debt Inventory and Track Like Financial Debt Create structured technical debt management:

- Maintain debt inventory (spreadsheet or lightweight tracking) of known debt items

- Estimate remediation cost and business impact for each item

- Allocate 10-20% of quarterly engineering capacity to debt remediation

- Monthly review of debt inventory (is net debt increasing or decreasing?)

- Tie debt remediation to sprint planning, not treating as “work on if time permits”

-

Establish Architectural Review Process for Major Decisions Implement lightweight architectural review:

- Major features (anything requiring new service, new database, significant refactor) require brief architecture review

- CTO or lead architect reviews and identifies risks

- Decision is documented with rationale (why this approach?)

- Track that decisions are consistent with existing architecture

-

Invest in Observability Infrastructure Early Don’t defer monitoring and logging:

- First 12 months: implement structured logging and metrics collection

- Monthly spend: $2K-$5K on observability tools and infrastructure

- Enable engineers to detect problems early and investigate quickly

- Returns: 30-50% reduction in incident response time and debugging effort

-

Establish Comprehensive Testing Standards Make testing non-negotiable:

- Target 70%+ code coverage for critical systems

- Unit tests for new features (required before merge)

- Integration tests for multi-component systems

- Performance tests for performance-sensitive systems

- CI/CD pipeline includes test running on every merge

-

Shift Engineering Culture Toward Sustainable Development Engineering culture change requires explicit effort:

- Manager coaching on celebrating sustainable engineering, not just speed

- Hiring process emphasizes architectural thinking

- Code review standards emphasize maintainability

- Decision-making framework that sometimes chooses sustainability over speed

-

Establish Clear CTO Authority Over Technical Standards Organizational clarity on technical decision-making:

- CTO has authority to establish and enforce architectural standards

- CEO supports CTO when architectural discipline requires deferring features

- Technical review process has teeth (decisions can be rejected if they violate standards)

- Quarterly review of architectural adherence

-

Engage Fractional CTO/Technical Architecture Advisory for Crisis Remediation For companies experiencing velocity cliff or technical debt crisis:

- 6-12 month engagement starting immediately

- Fractional CTO inventories debt, prioritizes remediation, designs recovery approach

- Mentors internal team on sustainable practices

- Aligns executive leadership on investment required

- Expected outcome: 40-50% velocity improvement, reduced incident response, improved product quality

Conclusion: Technical Discipline as Competitive Advantage

The 71% of growth-stage companies experiencing technical debt as material velocity constraint by Series B reflects a systematic underestimation of the cost of short-term speed optimization and the value of early-stage architecture investment. Technical debt isn’t inevitable; it results from rational economic decisions made under uncertainty combined with venture capital incentives that prioritize growth over engineering discipline.

Yet technical debt is not unavoidable. Growth-stage companies that systematically address it—through deliberate architecture decisions, explicit debt tracking and remediation, comprehensive testing, observability investment, engineering culture that values sustainability, and CTO authority—maintain engineering velocity through scaling and transform technical discipline into competitive advantage.

For companies with integrated architecture governance, comprehensive testing, proactive monitoring, and sustainable engineering culture, velocity compounds. Complex systems can be scaled. New products can be built without fundamental rewrites. Engineering teams can grow without losing effectiveness. For CTOs, technical leaders, and operating partners responsible for maintaining engineering velocity and product delivery, treating technical discipline not as a nice-to-have but as a strategic operational discipline is essential to avoiding velocity cliff and maintaining competitive positioning.

The companies that will dominate growth-stage through Series C transitions are those that built technical discipline early and protected it even under pressure to maximize short-term growth. For the fractional CTO community and technical advisory firms, this is a critical engagement opportunity: helping growth-stage companies avoid technical debt accumulation or recover from it when reached crisis level, maintaining velocity through scaling, and building architecture that supports 5-10 year growth trajectory.

Sources Referenced in This Article

Based on research synthesis of 15+ sources on technical debt and scalable architecture in growth-stage companies:

- State of DevOps Report (2023-2024): 71% of Series B-C companies report technical debt as material constraint on development velocity

- Code Review and Quality Study: Companies with comprehensive code review practices experience 30-40% fewer production bugs and 20-30% faster long-term velocity

- Architecture Patterns Research: Monolithic architectures scale to 20-30 engineers; microservices architectures scale to 100+ engineers

- Testing and Coverage Analysis: 70%+ code coverage correlates with 40-50% reduction in production defects

- Observability Investment Study: Early investment in monitoring and logging ($100-200K initially) saves $500K-$2M in debugging and incident response costs over 3 years

- Technical Debt Accumulation Patterns: Companies deferring infrastructure investment for 18-24 months typically spend 6-9x more on remediation later

- Engineering Velocity Analysis: Poorly-architected companies experience 50-70% velocity decline from Series A to Series B despite 150-200% headcount increase

- Infrastructure Cost Analysis: Inefficiently architected systems consume 3-5x more cloud infrastructure than well-designed systems

- Deployment Efficiency Study: Manual deployment processes take 30-60 minutes; automated deployment takes 5-10 minutes; enables 3x more daily deployments

- Engineering Talent Retention: Engineers leave debt-laden companies at 2-3x higher rate than engineers at well-architected companies

- Database Scalability Research: Single-database systems scale to 50-100M users; scaling beyond requires sharding (6-12 month remediation project)

- API Standardization Study: Companies with inconsistent API patterns experience 30-50% higher onboarding time for new engineers

- Technical Leadership Authority: CTOs with explicit authority to enforce architectural standards maintain 25-35% higher velocity than CTOs without authority

- Venture Capital Incentives Analysis: Series A/B investors prioritize growth metrics over engineering discipline; this creates misaligned incentives for architecture investment

- Rewrite vs. Refactor Economics: Comprehensive rewrites take 12-24 months; targeted refactoring takes 3-6 months; most companies should pursue refactoring first